Training Tools II: Physical Pressures

Heeding is very simple. The trainer introduces a pressure to the horse then pays close attention to how the horse perceives and reacts to it. Then the trainer modifies the pressure to help the horse develop a better connection between the pressure and the shape the trainer wants him to take.

In order to become horse trainers, students first need to understand the full range of pressures available to use as training tools. Then they must learn how to combine these individual pressures into corridors of pressures and learn how to apply these corridors methodically. Methodically means that the way the trainer applies the pressures creates a feeling in the horse of a shape he wants the horse to take and a direction he wants the horse to move. When each new corridor of pressures is just a step or two away from what the horse already understands, training is horse logical and meaningful.

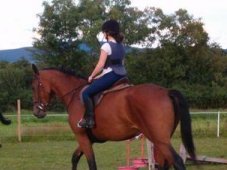

To help students start understanding the range of pressures they can use, we categorize pressures as either psychological or physical. We talked about the many psychological pressures trainers exert on horses from the minute they walk into a stall, catch a horse, groom him, and lead him, etc., in the preceding article. As riders, students arrive here with lots of experience with physical pressures. They use leg pressures and rein pressures and seat pressures and other kinds of physical pressures to get their horse to do or not do things. As riders, they understand what they intend those pressures to mean to the horse. But hardly any of them fully understand these pressures from the horse’s viewpoint.

A horse feels physical pressures as relative pressures. He is walking in a straight line and a shift in seat pressure make him feel like carrying his head over to one side a little. Or a squeeze from both legs makes the horse feel like contracting his belly muscles and lifting his back. The trainer applies the pressure long enough for the horse to figure out the shape it means. When the horse figures it out, the trainer removes the pressure as a reward to the horse.

Horses can also feel physical pressures as a startle or interruption of something they are already doing. Physical startle pressures are quick jabs or jerks that do not last. They can be used to help the horse refine a shape but only if the horse already understands the shape in the first place.

We produce both kinds of physical pressures by using natural or artificial aids. The reins, legs, and seat are the most commonly discussed natural aids. I include breathing among the physical pressures students can use to influence a horse. And some people would include the voice. Whips and spurs are the primary artificial aids. Some people would also include training devices like tie downs and chambons. On analysis, the division of pressures into natural and artificial is somewhat arbitrary.

Some people like to say that natural aids always create relative physical pressures and artificial aids always create startle pressures. But this is a bit arbitrary, too. A rein or a leg aid, even a seat aid, becomes a startle pressure if it is used abruptly or sharply so that it raises the horse’s excitement level. Keep in mind that how an individual horse perceives a pressure depends somewhat on his personality, on his trust in his trainer, and on where he is in the training progression.

In the same way, whips and spurs do not always startle. When they are used as an on/off correction or enforcement of something the horse already understands, they can reinforce a natural aid without interrupting the horse’s activity. When people constantly jab with their spurs or tap with a whip, that becomes a constant pressure that the horse learns to ignore. But the same thing happens when a rider has heavy hands or balances on their reins. The horse just learns to tune out the bit noise. Selective startle pressures are effective; repetitive startle pressures simply become part of the routine and the horse ignores them.

As students become more sophisticated in their application of psychological and physical pressures, it becomes evident that the distinction between the two kinds of pressures is not always clear cut. For example, if any one pressure in a corridor of pressures becomes startling or blatant, it cancels out all the other pressures in the corridor. So if a student applies a physical pressure in a startling way that raises the horse’s excitement level, the psychological result is that the whole corridor falls apart. That is why a really sharp bit can cancel out the effects of a trainer’s seat and legs.

Training a horse means methodically applying horse-logical pressures, paying close attention to the horse’s reaction to them, and then modifying those pressures to help the horse develop a better connection between them and the shape you want him to take. Horse-logical means the trainer uses the horse’s feelings to make the horse feel like doing what the trainer wants done. Training is that simple. And it is that complex.